Introduction

As usual, pull the files from the skeleton and make a new IntelliJ project.

This lab is on the long side, so make sure to pair program!

Similarly, the provided HashMapTest is fairly limited. We will discuss the suggested testing steps below, but ensure you are creating your own tests for all versions of your data structure. Note, do not import java.util.HashMap to make the red lines in Intellij go away. This will cause the tests to test Java’s official implementation of a HashMap. rather than yours.

In today’s lab, we’ll learn about an incredible data structure that can provide constant time insertion, removal, and containment checks. Yes, you read that correctly: constant, \(\Theta(1)\), runtime! In the best case scenario, the hash table can provide amortized constant time access to its elements regardless of whether we’re working with 10 elements, 1,000 elements, or 1,000,000 elements.

Before we jump into hash tables, we’ll first introduce a small example class, SimpleNameMap, that implements some of the basic ideas behind hash tables while incorporating the map abstract data type. Through the course of this lab, we will add new functionality to the SimpleNameMap to make it more robust. For this reason, you should perform some simple sanity checks (in the form of small unit tests) between each exercise to ensure you are working in the right direction. If you get stuck at any point, please ask your TA or an AI to clarify, as each step in this lab will build upon the next! We will also analyze the SimpleNameMap to see exactly how it works and why we need to make a distinction between the best and worst case runtimes.

Finally, we’ll implement a real HashMap by generalizing the lessons we learned in the process of developing the hash table in the SimpleNameMap. Along the way, we’ll also discuss the merits and drawbacks of Java’s hashCode, or hash function, and how we can design our own hash functions.

Fast Maps

Recall that we developed a binary search tree that acted as a Set back in lab 13 with the add and contains methods. It was certainly quite fast with \(O(\log N)\) add, contains, and remove assuming a balanced tree. But we can do even better!

How can we design a constant time implementation of Map? If you’re familiar with Python, a map is like a dictionary: it provides a mapping from some key (like a word in an English dictionary) to its value (like the definition for that word). It’s similar to a Set in that keys are guaranteed to be unique.

We need to design a data structure where, no matter how many elements we insert into the Map, we can still retrieve any single element in \(\Theta(1)\) time. If we were to use a binary search tree to maintain our mapping, it can take up to \(O(\log N)\) time to retrieve any single element because we may need to traverse \(\log N\) other nodes to reach a leaf at the bottom of the tree. Our goal, then, is to figure out how we can design a Map that does not need to consider any significant portion of other keys.

Which data structure have we seen before in class that provides constant-time access to any arbitrary element? Highlight to verify your answer:

We will need to make some changes to make it work with the Map interface, which we will explore throughout this lab, but note that arrays are fast. Unlike a linked list or a tree, there’s no need to traverse any part of the collection to reach an element: we can simply use bracket notation, array[i], to jump right to the ith index in constant time.

For the most part, this works great!

Consider the following implementation of a simple Map that maps first names (key) to last names (value). This Map associates a number with each key, and this number will refer to the index of the array that this key-value pair should be placed. In this scheme, we will let the first letter in each key determine its index in the final array. For example, if the key is “Alex”, the letter ‘A’ tells us that this key-value pair will map to array[0]. Listed below are our keys and values, and what index each key corresponds to:

| Key | Value | Array Index |

|---|---|---|

| “Alex” | “Schedel” | 0 |

| “Connor” | “Lafferty” | 2 |

| “Henry” | “Kasa” | 7 |

| “Jay” | “Kakkar” | 9 |

| “Matt” | “Owen” | 12 |

| “Parth” | “Gupta” | 15 |

| “Zoe” | “Plaxco” | 25 |

We can define this conversion in a hash function, whose job, when given a key, is to return a specific integer for that key. In this case, the hash function uses the first character of the name to figure out the correct integer to return.

public class String {

public int hashCode() {

return (int) (this.charAt(0) - 'A');

}

}

(Casting an character to an int converts the character into the “associated” number. What is this associated number? The ASCII table provides an encoding of letters, starting with capitol letters, and A is encoded as value 65. We subtract 'A' because we want our letters to start at zero, rather than 65.)

When we are given this integer, we can then treat it as the index where the key-value pair should go in the array!

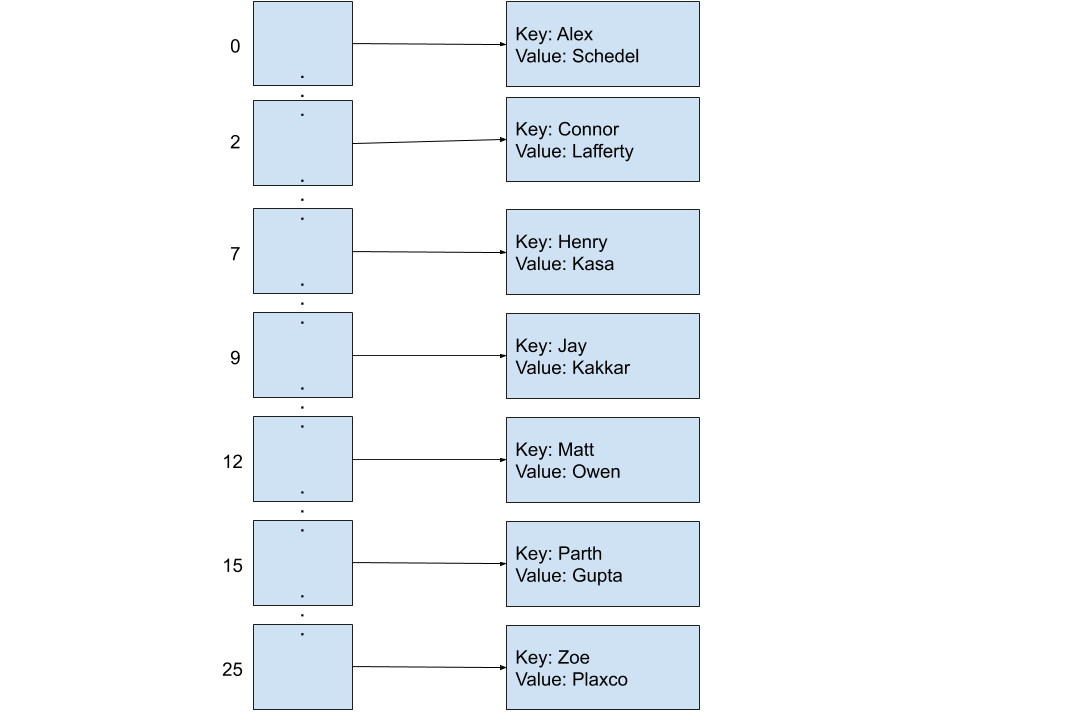

Now, if we were to put the key-value pairs in the array, it would look as follows:

Since we know exactly which index each String will map to, there’s no need to iterate across the entire array to find a single element! For example, if we put “Parth Gupta” into the map (in the map, this entry will appear as (“Parth”, “Gupta”)), we can find it later by simply indexing to array[15] because Parth’s ‘P’ lives in the fifteenth array entry. Insertion, removal, and retrieval of a single element in this map, no matter how full, will only ever take constant time because we can just index based on the first character of the key’s name.

Now that we’ve talked a little bit about this map, let’s return to hash tables. Our map above is actually implementing the foundational ideas of hash tables. Hash tables are array-backed data structures and use the integer returned by an object’s hash function to find the array index of where that object should go. In our map, we hash our key and use the return value to figure out where to put our key-value pair. We’ll learn more about how the hash function plays into the hash table later on in the lab.

Exercise 1: SimpleNameMap

In SimpleNameMap.java, implement the array-backed data structure based on the details listed above. To do so, fill in a constructor that initially creates 26 empty spaces in the array-backed data structure, add any instance variables, and implement the following methods:

public boolean containsKey(String key);

public String get(String key);

public void put(String key, String value);

public String remove(String key);

We’ve started you off with a very basic skeleton containing an Entry static nested class used to represent an entry (a key-value pair) in our map.

You may also want to write your own hash(String key) function that works like the String.hashCode() example introduced above to simplify the code you write. Remember that we need to subtract 'A' when hashing so that the zero-indexing will work correctly!

Assume for this part of the lab that all keys will be valid names, and all keys inserted into this map will start with a different (unique) letter.

Test

Before you move on, ensure that your SimpleNameMap works as you intend it to. Create a small unit test and insert a few items. Use the debugger and assert statements to ensure that elements are properly added and removed. You should also separately test your implementation of containsKey!

Not Quite Perfect

Now that we’ve completed a basic implementation of SimpleNameMap, can you spot any problems with the design? Consider what happens if we try to add a few more of the current staff members to the map. Below, we have a table of the name to array index mapping.

| Key | Value | Array Index |

|---|---|---|

| “Ada” | “Hu” | 0 |

| “Alex” | “Schedel” | 0 |

| “Connor” | “Lafferty” | 2 |

| “Henry” | “Kasa” | 7 |

| “Jay” | “Kakkar” | 9 |

| “John” | “Xiang” | 9 |

| “Mike” | “Chou” | 12 |

| “Matt” | “Owen” | 12 |

| “Parth” | “Gupta” | 15 |

| “Zoe” | “Plaxco” | 25 |

What are some of the drawbacks of the SimpleNameMap?

If we simply try to add all the elements in the table above to the map, what will happen?

What if we want to use lowercase letters or special characters as the first letter of the name? Or any character, ever, in any language?

And, how can we use this structure with objects other than strings?

Listed below are some of the problems that the current SimpleNameMap faces:

-

Collisions: Alex and Ada share index 0 while Jay and John share index 9. What happens if we need to include multiple A-names or J-names in our

SimpleNameMap? -

Memory inefficiency: The size of our array needs to grow with the size of the alphabet. For English, it’s convenient that we can just use the first letter of each name as the array index so we only need 26 spaces in our array. However in other languages, that might not be true. To support any possible symbol, we might need an array with a length in the thousands or millions to ensure complete compatibility, even though we may only need to store a handful of names.

-

Hashing: How do we generalize the indexing strategy in

SimpleNameMap? The underlying principle behind hashing is that it provides a scheme for mapping an arbitrary object to an integer. ForStringnames, we can get away with using the first character, but what about other objects? How can we reliably hash an object like aPotato?

We’ll see later that all three of these points above play a large role in the runtime and efficiency of a hash table. For the remainder of this lab, we will be extending the SimpleNameMap to workaround each of these limitations before implementing a fully-fledged HashMap that implements interface Map61BL.

The Hash Table

Collisions

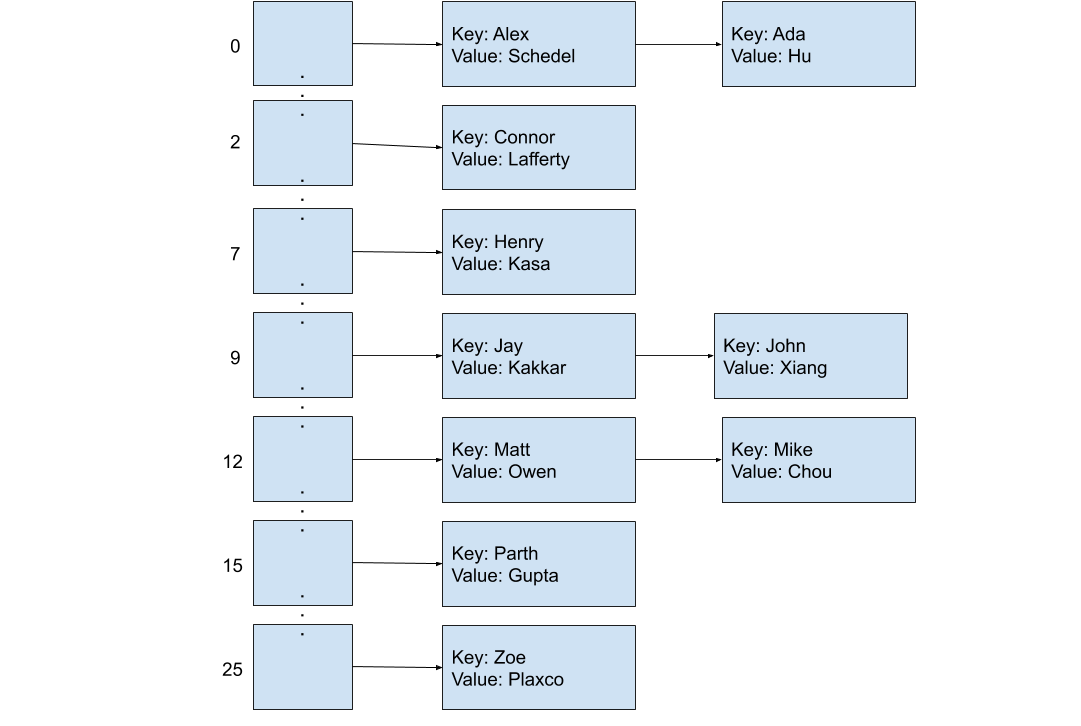

In the previous example, the keys had mostly different values, but there were still several collisions caused by distinct keys sharing the same hash value. “Alex” and “Ada” are both distinct keys but they happen to map to the same array index, 0, just as “Jay” and “John” share the index 9. Other hash functions, like one depending on the length of the first name, could produce even more collisions depending on the particular data set.

There are two common methods of dealing with collisions in hash tables, which are listed below:

-

Linear Probing: Store the colliding keys elsewhere in the array, potentially in the next open array space. This method can be seen with distributed hash tables, which you will see in later computer science courses that you may take.

-

External Chaining: A simpler solution is to store all the keys with the same hash value together in a collection of their own, such as a linked list. This collection of entries sharing a single index is called a bucket.

We primarily discuss external chaining implemented using linked lists in this course. Here are the example entries from the previous step, hashed into a 26-element map of linked lists using the function based on the first letter of the string as defined earlier (the hashCode function is duplicated below for your convenience).

public class String {

public int hashCode() {

return (int) (this.charAt(0) - 'A');

}

}

Inserting ("Ada", "Hu") into this map after previously inserting ("Alex", "Schedel") appends Ada’s entry to the end of the linked list at that index.

Hint: Ensure you are using .equals() rather than == to test the equality of two Objects!

Discussion: Runtimes

Now for a bit of runtime analysis!

For the following two scenarios, determine with your partner the worst case runtime of getting a key with respect to the total number of keys, \(N\), in the map and explain your answer to each other. Assume our hash map implements external chaining.

-

All of the keys in the map have different hash codes and get added to different indices in the array. An example input might look like:

("Eli", "Lipsitz"), ("Grace", "Altree"), ("Shreya", "Sahoo"), ("Travis", "Reyes"). -

All the keys in the map have the same hash code (despite being different keys), and they get added to the same bucket. An example input might look like: `(“Christopher”, “Zou”), (“Connor”, “Lafferty”), and (“Claire”, “Ko”).

If you have any questions, double check with your TA before moving on!

Exercise 2: External Chaining

First, switch which partner is coding for this part of the lab. Then, let’s add external chaining to our SimpleNameMap.

To implement external chaining, we can use Java’s LinkedList class. You’ll need to put in a little work to get it working with Java arrays, so see this StackOverflow post and this one as well for workarounds.

In addition, make changes to the following functions to support external chaining:

public boolean containsKey(String key);

public String get(String key);

public void put(String key, String value);

public String remove(String key);

Remember that any class that implements Map cannot contain duplicate keys.

Hint: ensure you are initializing your LinkedLists at instantiation.

Memory Inefficiency

Another issue that we discussed is memory inefficiency: for a small range of hash values, we can get away with an array that individuates each hash value. This works well if our indices are small and close to zero. But remember that Java’s 32-bit integer type can support numbers anywhere between -2,147,483,648 and 2,147,483,647. Now, most of the time, our data won’t use anywhere near that many values. But even if we only wanted to support special characters, our array would still need to be 1,112,064 elements long!

Instead, we’ll slightly modify our indexing strategy. Let’s say we only want to support an array of length 10 so as to avoid allocating excessive amounts of memory. How can we turn a number that is potentially millions or billions large into a value between 0 and 9, inclusive?

The modulo operator allows us to do just that. The result of the modulo operator is like a remainder. For example, 65 % 10 = 5 because, after dividing 65 by 10, we are left with a remainder of 5. Note that you can read the expression as “65 mod 10”. Thus, 3 % 10 = 3, 20 % 10 = 0, and 19 % 10 = 9. Returning to our original problem, we want to be able to convert any arbitrary number to a value between 0 and 9, inclusive. Given our discussion on the modulo operator, we can see that any number mod 10 will return an integer value between 0 and 9. This is exactly what we need to index into an array of size 10!

More generally, we can locate the correct index for any key with the following,

Math.floorMod(key.hashCode(), array.length)

where array is the underlying array representing our hash table.

In Java, the floorMod function will perform the modulus operation while correctly accounting for negative integers, whereas % does not.

Exercise 3: Modulo

Make changes to the following functions to support modulo.

public boolean containsKey(String key);

public String get(String key);

public void put(String key, String value);

public String remove(String key);

Hashing

The last problem of our SimpleNameMap was that not all objects can be easily converted into a number. However, the idea underlying hashing is the transformation of any object into a number. If this transformation is fast and different keys transform into different values, then we can convert that number into an index and use that index to index into the array. This will allow us to approximate the direct, constant-time access that an array provides, resulting in near constant-time access to elements in our hash table.

The transforming function is called a hash function, and the int return value is the hash value. In Java, hash functions are defined in the object’s class as a method called hashCode() with return value int. The built-in String class, for example, might have the following code.

public class String {

public int hashCode() {

...

}

}

This way, we can simply call key.hashCode() to generate an integer hash code for a String instance called key.

Exercise 4: hashCode()

First, switch which partner is coding for this part of the lab. Then, modify our SimpleNameMap so that, instead of using the first character as the index, we instead use key’s hashCode() method.

Make changes to the following functions to support using a key’s hashCode().

public boolean containsKey(String key);

public String get(String key);

public void put(String key, String value);

public String remove(String key);

Note that, to use hashCode()’s results as an index, we must convert the returned hash value to a valid index. Because hashCode() can return negative values, use the floorMod operation discussed above!

If you created a hash function from earlier to help hash your Strings, you can now delete this (we have a better hashCode() function now!).

Hash Function Properties

We learned earlier that collisions are troublesome: exactly how many collisions occur makes the difference between a pretty good runtime and a not so good runtime. We need a hash function that distributes our keys as evenly as possible throughout the map in order to reduce the number of collisions so we can guarantee a close to constant time runtime for all of our operations.

But first off, what hash functions can we choose from? Are all functions that return a number for each object a valid hash function? What makes a hash function good?

A hash function is valid if:

- The hash function of two objects A and B (who are equal to each other according to their

.equals()method) are the same value. We call this requirementdeterminism. - The hash function returns the same integer every time it is called on the same object. We call this requirement

consistency.

Note that there are no requirements that state that unequal items should have different hash function values.

The properties of a good hash function is less defined, but here are some properties that are important for a good hash function (this is a non-exhaustive list):

- The hash function should be valid.

- Hash function values should be spread as uniformly as possible over the set of all integers.

- The hash function should be relatively quick to compute. (Don’t worry too much about the specifics of this if this sounds vague to you. Just be aware that the hash function should not be unreasonably expensive to compute relative to the size of what you are hashing.)

If you have any other ideas about what makes a good hash function, be sure to check in with your TA!

Load Factor

No matter what, if the underlying array of our hash table is small and we add a lot of keys to it, then we will start getting more and more collisions. Because of this, a hash table should expand its underlying array once it starts to fill up (much like how an ArrayList expands once it fills up).

To keep track of how full our hash table is, we define the term load factor, which is the ratio of the number of entries over the total physical length of the array.

\[\text{load factor} = \frac{\texttt{size()}}{\texttt{array.length}}\]For our hash table, we will define the maximum load factor that we will allow. If adding another key value pair would cause the load factor to exceed the specified maximum load factor, then the hash table should resize. This is usually by doubling the underlying array length. Java’s default maximum load factor is 0.75 which provides a good balance between a reasonably-sized array and reducing collisions.

Note that if we are trying to add a key-value pair and the key already exists in the hash map, the corresponding value should be updated but no resizing should occur.

As an example, let’s see what happens if our hash table has an array length of 10 and currently contains 7 elements. Each of these 7 elements are hashed modulo 10 because we want to get an index within the range of 0 through 9. The current load factor is \(\frac{7}{10}\), or 0.7, just under the threshold.

If we try to insert one more element, we would have a total of 8 elements in our hash table and a load factor of 0.8. Because this would cause the load factor to exceed the maximum load factor, we must resize the underlying array to length 20 before we insert the element. Remember that since our procedure for locating an entry in the hash table is to take the hashCode() % array.length and since our array’s length has changed from 10 to 20, all the elements in the hash table need to be relocated. Once all the elements have been relocated and our new element has been added, we will have a load factor of \(\frac{8}{20}\), or 0.4, which is below the maximum load factor.

Exercise 5: Resizing

Update SimpleNameMap to include the automatic resizing feature described above. For the purposes of this assignment, only implement resizing upwards from smaller arrays to larger arrays. (Java’s HashMap also resizes downward if enough entries are removed from the map.)

To do this, you will need add a method to keep track of the size of the SimpleNameMap (size is the number of items inside the map, not the length of the underlying array) and store what the maximum load factor is for this map (use doubles to represent your load factors). The signature for the size() method is given below.

public int size();

In addition, make changes to the put function to support resizing. The signature for the put method is given below.

public void put(String key, String value);

A couple notes:

- It might help to write a

resizehelper method instead of trying to cram all the details intoput! - Remember that you should only resize if the addition introduces a new key (updating old key-value pairs do not count) and you should check if you need to resize before adding the new element.

- Dividing an integer by another integer will round your result down to the nearest integer.

Exercise 6: HashMap

We’ve covered all the basics in a hash map. Now, let’s write HashMap.java! Or, rather, since we’ve already written SimpleNameMap.java, let’s just make the necessary changes to generalize the code to comply with theMap61BL interface.

First, switch which partner is coding for this portion of the lab. Then, copy SimpleNameMap.java to a file named HashMap.java and modify the type parameters everywhere in the code so that the key and value are generic types. For example, the class header might read:

public class HashMap<K, V> implements Map61BL<K, V>

You will need to add generic type parameters to your Entry class as well (just as we did for HashMap, and replace all instances of Entry in your code with Entry<K, V> (or whatever generic variables to intend on using).

In addition, modify the parameters and return values of the methods.

Then, add and implement the remaining functions of the Map61BL interface, listed below:

// Descriptions of what each method should do can be found in the Map61BL

// interface.

public void clear();

public boolean remove(K key, V value);

public Iterator<K> iterator();

Implementing the iterator() method is optional, but the skeleton and tests have been provided for you if you want the additional practice implementing iterators. If you choose not to implement this method, have the iterator() method throw a new UnsupportedOperationException.

If you choose to implement iterator(), you may find it useful to write another inner class, as we have done in previous labs. Because remove of the Iterator interface is an optional method, the iterator does not need to have it implemented and you may throw an UnsupportedOperationException in that case.

To speed up testing, we’ve provided the full test suite in the skeleton. Our tests expect a couple of extra constructors and methods (listed below) so make sure to implement these in your HashMap as well.

/* Creates a new hash map with a default array of size 16 and a maximum load factor of 0.75. */

HashMap();

/* Creates a new hash map with an array of size INITIALCAPACITY and a maximum load factor of 0.75. */

HashMap(int initialCapacity);

/* Creates a new hash map with INITIALCAPACITY and LOADFACTOR. */

HashMap(int initialCapacity, double loadFactor);

/* Returns the length of this HashMap's internal array. */

public int capacity();

Discussion: Wrap Up

We have now finished the main part of the lab, though here are a few miscellaneous questions that you may have come up with throughout the course of the lab.

-

We’ve learned that external chaining is one method for resolving collisions in our hash table. But why use a linked list? Why not use an array instead? What are the benefits and drawbacks of each?

-

How does the load factor play a part in this? Assuming that the keys are perfectly distributed, how many entries should be in each bucket and how does this affect the runtime?

-

Additionally, we forgot to put two staff members, “Alex Schedel” and “Alex Feng”, into our map! However, if we tried to put both of them into our map, they would override each other’s entries since keys must be unique. Is it possible to modify our data structure so that both people can be in the map? If not, what other data structures can we use so we can store all the staff members?

Discuss all these questions with your partner, and make sure to ask the lab staff if you have any questions.

Conclusion

A Discussion of Runtime

So now you’ve implemented your HashSet (or at least read the spec) and (hopefully) satisfied the runtime constraints. We have seen other data structures in this class which rarely have such good runtime. How can we store so many elements efficiently with such good runtime? How do our decisions about when and how to resize affect this?

For an intuitive metaphor for this, check out Amortized Analysis (Grigometh’s Urn).

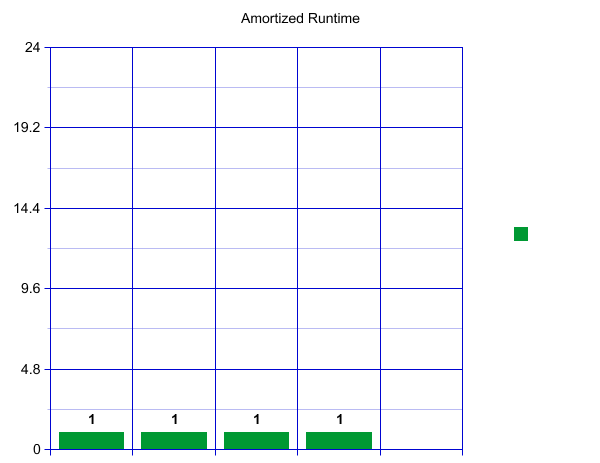

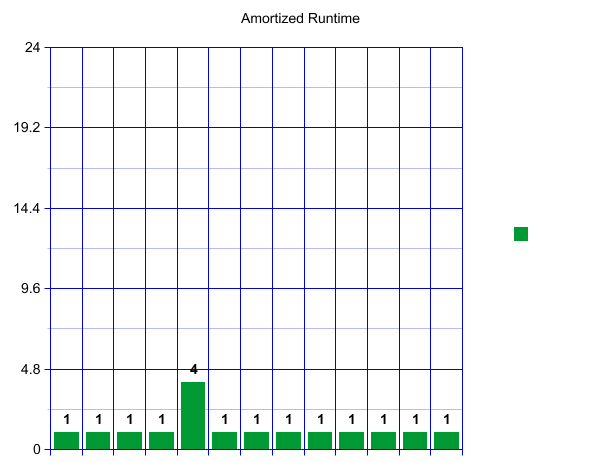

If you are more visually inclined, here is one way to visualize the runtime in the form of a graph. We’ll assume here that our hashcode is very good and we don’t get very many collisions (a powerful assumption). When we first create our HashSet, let’s say we decide to start with an outer array of size 4. This means we can have constant runtime for our first four insertions. Each operation will only take one unit of time.

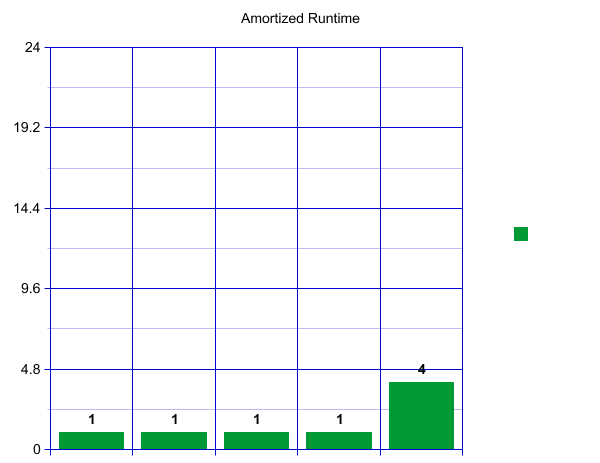

When we reach our load factor and have to resize, let’s say we decide to make an array of size 8 and copy over our four current items—which takes four constant time lookups.

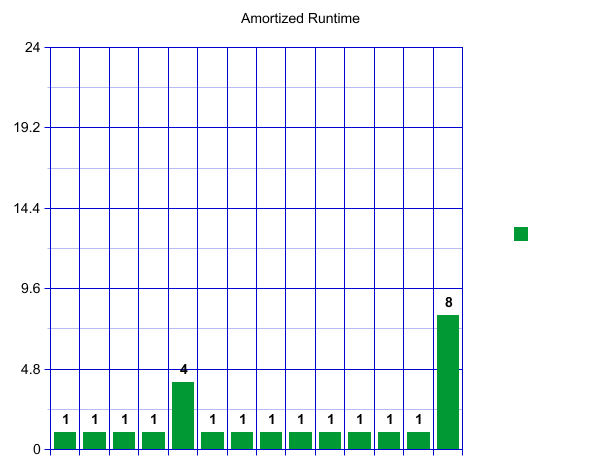

That is a big spike! How can we say this is constant? Well, we will now have eight fast inserts! Wow!

A pattern starts to emerge. Once we have again reached our load factor there will be a spike, followed by a sequence of “inexpensive” inserts. These spikes, however, are growing rapidly!

If we imagine this continuing, each spike will get bigger and bigger! Perhaps counter intuitively, this runtime, viewed over a long time, is actually constant if the work is “amortized” over all of our inserts. Here amortized means that we are spreading the cost of an expensive operation over all our operations. This gives us a constant runtime overall for a large sequence of inserts and resizes. To convince yourself of this visually, imagine “tipping” the size four spike so that it adds one operation to each of the four fast inserts before it. Now each insert operation is taking about 2 units of work, which is constant! We can see this pattern will continue. We can “tip” our size eight resize across the eight previous fast operations! Try drawing a few more resizes out and convince yourself that the spike will always fit.

We have now gotten to the heart of the efficacy of HashSets. Would we get this behavior if we picked a resizing scheme which was additive and not multiplicative? Discuss with your partner and then highlight to verify your answer:

No! It must be a multiplicative resize scheme. Try drawing the same graphs with an additive scheme. Do the spikes match the valleys? Nope! .

Summary

In this lab, we learned about hashing, a powerful technique for turning a complex object like a String into a smaller, discrete value like a Java int. The hash table is a data structure which combines this hash function with the fact that arrays can be indexed in constant time. Using the hash table and the map abstract data type, we can build a HashMap which allows for amortized constant time access to any key-value pair so long as we know which bucket the key falls into.

However, we quickly demonstrated that this naive implementation has several drawbacks: collisions, memory inefficiencies, and the hash function itself. To workaround each of these challenges, we introduced three different features:

-

We added external chaining to solve collisions by allowing multiple entries to live in a single bucket.

-

To allow for smaller array sizes, we used the modulo operator to shrink hash values down to within a specified range.

-

Lastly, we designed and used different

hashCode()functions to see how different hash functions distributed keys and how it affects the runtime of the hash table.

Optional wrap up video

Deliverables

Complete the implementation of HashMap.java with:

- external chaining,

- the modulus operator,

- use of the

hashCodemethod, - resizing, and

- miscellaneous methods of the

Map61BLinterface.