Introduction

As usual, pull the files from the skeleton and make a new IntelliJ project.

Linked lists \(\subseteq\) Trees \(\subseteq\) Graphs

One of the first data structures we studied in this course was the linked list, which consisted of a set of nodes connected in sequence. Then, we looked at trees, which were a generalized version of linked lists. We can consider a tree as a linked list if we relaxed the constraint that a node could only have one child. Now, we’ll look at a generalization of a tree, called a graph. We can consider a graph as a tree if we relaxed the constraint that we can’t have cycles.

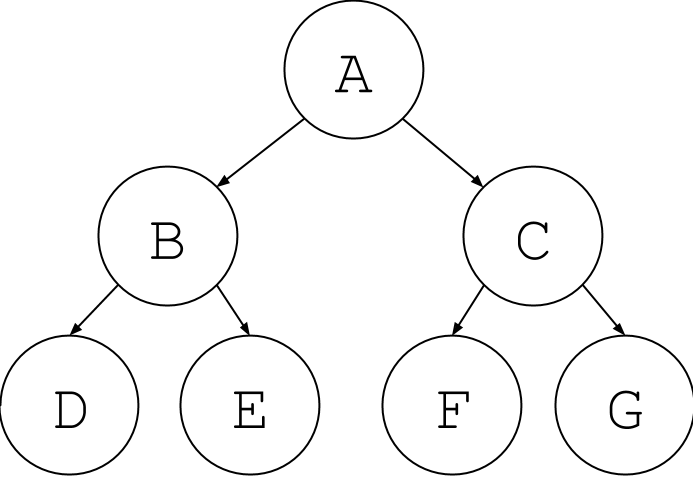

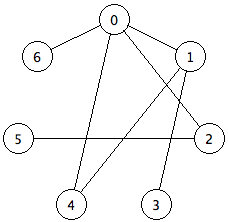

In a graph, we still have a collection of nodes, but each node in a graph can be connected to any other node without limitation. This means there isn’t necessarily a hierarchical structure like we get in a tree. For example, here’s a tree, where every node is descendant from one another:

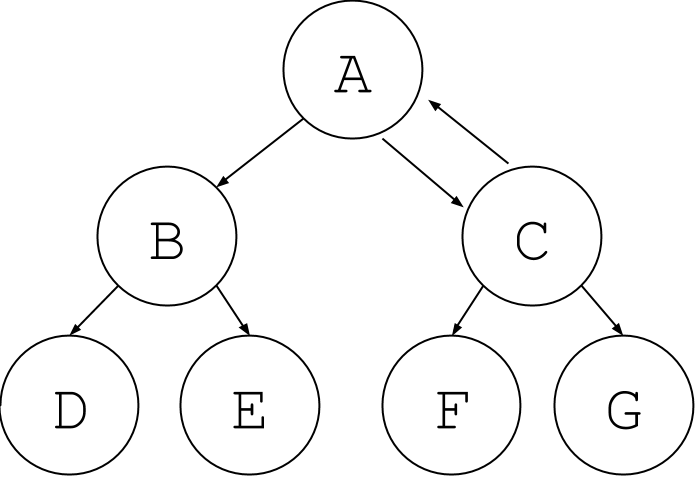

Now suppose we add an edge back up the tree, like this:

Notice the hierarchical structure is broken. Is \(C\) descendant from \(A\) or is \(A\) descendant from \(C\)? This is no longer a tree, but it is still a graph!

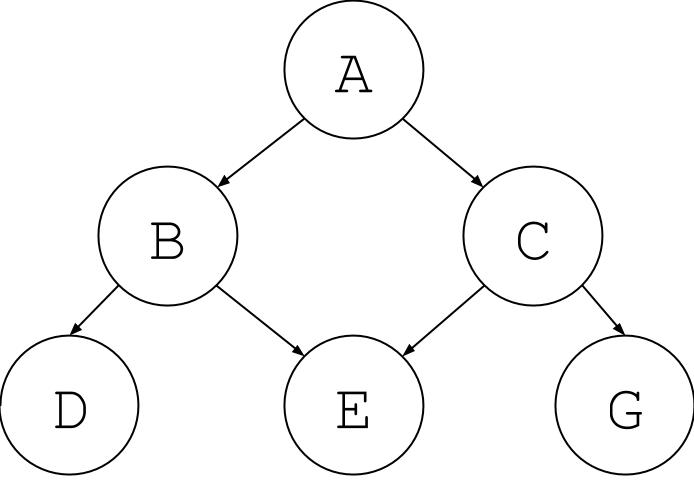

There are other edges that are not allowed in a tree, but are allowed in a graph. Let’s take a look at the following:

Now, node E looks like it is descendant from two nodes. Again, this is no longer a tree but it is a graph.

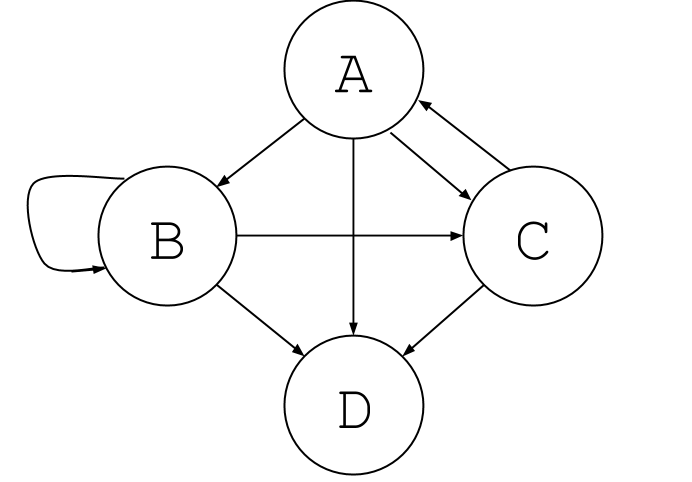

In general, a graph can have any possible connection between nodes, as shown below:

Graphs

Graphs are a good way to represent relationships between objects. First, let’s go over some terminology. A node in a graph is called a vertex. Vertices usually represent the objects in our graph (the things that have the relationships such as people, places, or things). A relationship between two vertices is represented by an edge.

Here are a few examples of graphs in the everyday world:

-

Road maps are a great example of graphs. Each city is a vertex, and the edges that connect these vertices are the roads and freeways that connect the cities. An abstract example of what such a graph would look like can be found here. For a more local example, each building on the Berkeley campus can be thought of as a vertex, and the paths that connect those buildings would be the edges.

-

Computer networks are also graphs. In this case, computers and other network machinery (like routers and switches) are the vertices, and the edges are the network cables. For a wireless network, an edge is an established connection between a single computer and a single wireless router.

Directed vs. Undirected Graphs

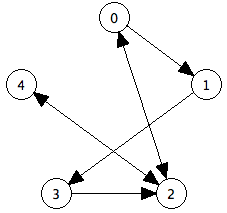

If all edges in a graph are showing a relationship between two vertices that works in both directions, then it is called an undirected graph. A picture of an undirected graph looks like this:

But not all edges in graphs are the same. Sometimes the relationships between two vertices only go in one direction. Such a relationship can be represented with a directed graph. An example of this could be a city map, where the edges are sometimes one-way streets between locations. A two-way street would have to be represented as two edges, one of them going from location \(A\) to location \(B\), and the other from location \(B\) to location \(A\).

Visually, an undirected graph will not have arrow heads on its edges because the edge connects the vertices in both directions. A directed graph will have arrow heads on its edges that point in the direction the edge is going. An example of a directed graph appears below.

Every undirected graph is a directed graph, but the converse is not true.

Graph Definitions

Now that we have the basics of what a graph is, here are a few more terms that might come in handy while discussing graphs.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adjacent | A vertex u is adjacent to a vertex v if u has an edge connecting to v. |

| Connected | A graph is connected if every vertex has a path to all other vertices. |

| Neighbor | A vertex u is a neighbor of a vertex v if they are adjacent. |

| Incident to an edge | A vertex that is an endpoint of an edge is incident to it |

| Indegree | A vertex v’s indegree is the number of vertices u that have an edge (u, v). |

| Path | A path is a sequence of edges from one vertex to another where no edge or vertex is repeated. |

| Cycle | A cycle is a path that ends at the same vertex where it originally started. |

Exercise: Edge vs. Vertex Count

For the following questions, discuss your solution with your partner and after verify your answer by highlighting the space after the question.

Exercise 1

Suppose that \(G\) is a directed graph with \(N\) vertices. What’s the maximum number of edges that \(G\) can have? Assume that a vertex cannot have an edge pointing to itself, and that for each vertex \(u\) and \(v\), there is at most one edge \((u, v)\).

Options:

\[N, N^2, N(N-1), \frac{N(N-1)}{2}\]Solution:

N(N-1).

Exercise 2

Now suppose the same graph \(G\) in the above question is an undirected graph. Again assume that no vertex is adjacent to itself, and at most one edge connects any pair of vertices. What’s the maximum number of edges that \(G\) can have compared to the directed graph of \(G\)?

Options:

- half as many edges

- the same number of edges

- twice as many edges

Solution:

half as many edges .

Exercise 3

What’s the minimum number of edges that a connected undirected graph with N vertices can have?

Options:

\[N - 1, N, N^2, N(N-1), \frac{N(N-1)}{2}\]Solution:

N-1 .

Graph Representation

Now that we know how to draw a graph on paper and understand the basic concepts and definitions, we can now consider how a graph should be represented inside of a computer. We want to be able to get quick answers for the following questions about a graph:

- Are given vertices

uandvadjacent? - Is vertex

vincident to a particular edgee? - What vertices are adjacent to

v? - What edges are incident to

v?

Most of today’s lab will involve thinking about how fast and how efficient each of these operations is using different representations of a graph.

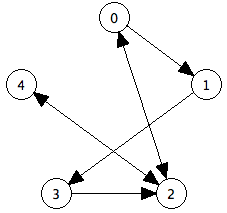

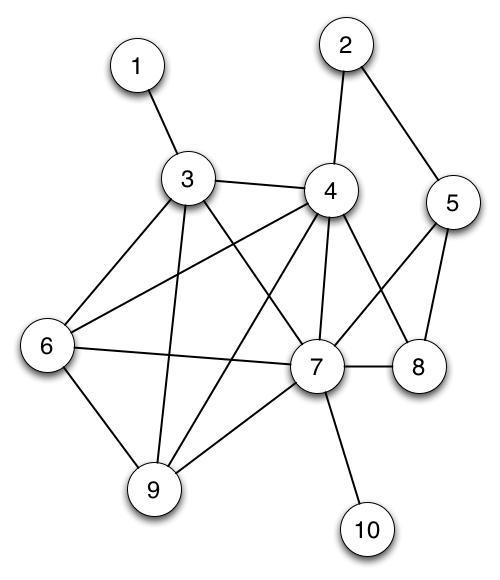

Imagine that we want to represent a graph that looks like this:

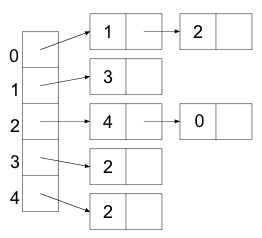

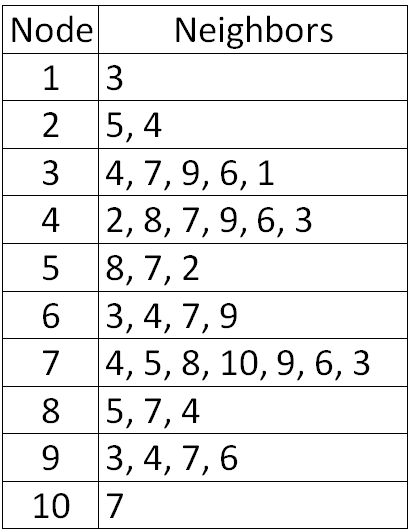

One data structure we could use to implement this graph is called an array of adjacency lists. In such a data structure, an array is created that has the same size as the number of vertices in the graph. Each position in the array represents one of the vertices in the graph. Each of these positions point to a list. These lists are called adjacency lists, as each element in the list represents a neighbor of the vertex.

The array of adjacency lists that represents the above graph looks like this:

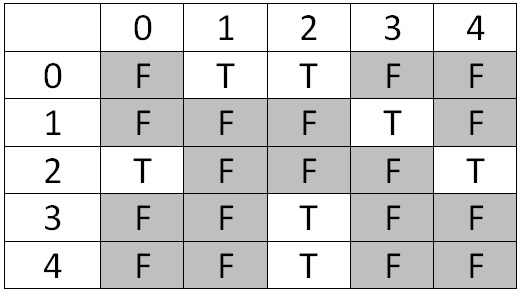

Another data structure we could use to represent the edges in a graph is called an adjacency matrix. In this data structure, we have a two dimensional array of size \(N \times N\) (where \(N\) is the number of vertices) which contains boolean values. The (i, j)th entry of this matrix is true when there is an edge from i to j and false when no edge exists. Thus, each vertex has a row and a column in the matrix, and the value in that table says true or false whether or not that edge exists.

The adjacency matrix that represents the above graph looks like this:

What will this matrix will look like for an undirected graph? Discuss with your partner. Considering drawing out the matrix and trying to notice some patterns.

Discussion: Representation

A third data structure we could use to represent a graph is simply an extension of the linked nodes idea. We can create a Vertex object for each vertex in the graph, and each of Vertex will contain pointers to the Vertex objects of their neighbors. This may seem like the most straightforward approach: aren’t the adjacency list and adjacency matrix roundabout in comparison?

Discuss with your partner reasons for why the adjacency list or adjacency matrix might be preferred for a graph.

Additionally, we could also represent a tree using an adjacency matrix or list. Discuss with your partner reasons for why an adjacency list or adjacency matrix might not be preferred for a tree.

Now, which is more efficient: an adjacency matrix or an array of adjacency lists?

Exercise: Graph.java

We have given you framework code for a class Graph. It implements a graph of integers using adjacency lists.

Fill in the following methods:

public void addEdge(int v1, int v2, int weight);

public void addUndirectedEdge(int v1, int v2, int weight);

public boolean isAdjacent(int from, int to);

public List<Integer> neighbors(int vertex);

public int inDegree(int vertex);

Graph Traversals

Earlier in the course, we used the general traversal algorithm to process all elements of a tree:

Stack<TreeNode> fringe = new Stack<>();

fringe.push(root);

while (!fringe.isEmpty()) {

TreeNode node = fringe.pop();

process(node);

fringe.push(node.right);

fringe.push(node.left);

}

The code above processes the tree’s values in depth-first order. If we wanted a breadth-first traversal of a tree, we’d replace the Stack with a queue such as a LinkedList.

Now, how would we modify this algorithm to traverse a graph?

Analogous code to process every vertex in a connected graph may look something like:

Stack<Vertex> fringe = new Stack<>();

fringe.push(startVertex);

while (!fringe.isEmpty()) {

Vertex v = fringe.pop();

process(v);

for (Vertex neighbor: v.neighbors) {

fringe.push(neighbor);

}

}

However, this doesn’t quite work. Unlike trees, a graph may contain a cycle of vertices and as a result, the code will loop infinitely.

We don’t want to process the same vertex more than once, so the fix is to keep track of vertices that we’ve put on our fringe and the vertices that we’ve visited already. Here is the correct pseudocode for graph traversal:

Stack<Vertex> fringe = new Stack<>();

HashSet<Vertex> visited = new HashSet<>();

fringe.push(startVertex);

while (!fringe.isEmpty()) {

Vertex v = fringe.pop();

if (!visited.contains(v)) {

process(v);

for (Vertex neighbor: v.neighbors) {

fringe.push(neighbor);

}

visited.add(v);

}

}

Note that the choice of data structure for the fringe can change. As with tree traversal, we can visit vertices in depth-first or breadth-first order merely by choosing a stack or a queue to represent the fringe. Typically though, because graphs are usually interconnected, the ordering of vertices can be scrambled up quite a bit. Thus, we don’t worry too much about using a depth-first or a breadth-first traversal. Instead, in the next lab session we will see applications that use a priority queue to implement something more like best-first traversal.

Note for the Exercises: Instead of checking that the popped vertex v is not yet visited, you can do this check before adding some neighbor to the fringe as well! This would look something like !visited.contains(neighbor). Although it is convention to check that the popped vertex is not yet visited, you may find this alternative way easier to code when you do the DFSIterator exercise later in the lab.

Exercise: Practice Graph Traversal

Use the graph traversal pseudocode from above to answer the following questions. It might help you to print out copies of the graph here. Now, figure out the order in which the nodes are visited if you start at different vertices. You should visit nodes in ascending order based on their natural ordering. You can check your answers for starting at vertices 1 - 5 below.

Answers for Practicing Graph Traversal

Here are the solutions for nodes 1-5 (just practice these until you feel comfortable).

| Starting vertex | Order of visiting remaining vertices |

|---|---|

| 1 | 3, 4, 2, 5, 7, 6, 9, 8, 10 |

| 2 | 4, 3, 1, 6, 7, 5, 8, 9, 10 |

| 3 | 1, 4, 2, 5, 7, 6, 9, 8, 10 |

| 4 | 2, 5, 7, 3, 1, 6, 9, 8, 10 |

| 5 | 2, 4, 3, 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

Read the code: DFSIterator

Read through the DFSIterator inner class. As its name suggests, it iterates through all of the vertices in the graph in DFS order, starting from a vertex that is passed in as an argument.

Note: This iterator may not print out all the vertices in the graph if they are unreachable from the starting vertex, and that’s okay!

Exercise: pathExists

Complete the method pathExists in Graph.java, which returns whether or not any path exists that goes from start to stop. Remember that a path is any set of edges that exists which you can follow that such you travel from one vertex to another by only using valid edges. Additionally, you may use the generateGX methods to generate some sample Graphs to test your implementation for this method (and the following methods)!

In addition, paths may not visit an edge or a vertex more than once. You may find it helpful for your method to call the dfs method, which uses the DFSIterator class.

Exercise: path

Now you will actually find a path from one vertex to another if it exists. Write code in the body of the method named path that, given a start vertex and a stop vertex, returns a list of the vertices that lie on the path from start to stop. If no such path exists, you should return an empty list.

Hint: Base your method on dfs, with the following differences. First, add code to stop calling next when you encounter the finish vertex. Then, trace back from the finish vertex to the start, by first finding a visited vertex u for which (u, finish) is an edge, then a vertex v visited earlier than u for which (v, u) is an edge, and so on, finally finding a vertex w for which (start, w) is an edge (isAdjacent may be useful here!). Collecting all these vertices in the correct sequence produces the desired path. We recommend that you try this by hand with a graph or two to see that it works.

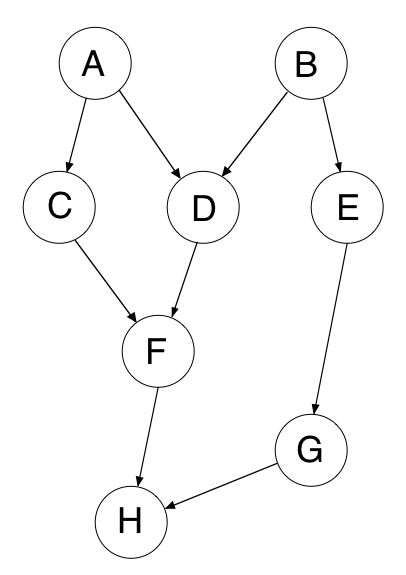

Topological Sort

A topological sort (sometimes also called a linearization) of a graph is a ordering of the vertices such that if there was a directed path from vertex v to vertex w in the graph, then v precedes w in the ordering.

This only works on directed, acyclic graphs, and they are commonly referred to by their acronym: DAG.

Here is an example of a DAG:

In the above DAG, a few of the possible topological sorts could be:

A B C D E F G H

A C B E G D F H

B E G A D C F H

Notice that the topological sort for the above DAG has to start with either A or B, and must end with H. (For this reason, A and B are called sources, and H is called a sink.)

Another way to think about it is that the vertices in a DAG represent a bunch of tasks you need to complete on a to-do list. Some of those tasks cannot be completed until others are done. For example, when getting dressed in the morning, you may need to put on shoes and socks, but you can’t just do them in any order. The socks must be put on before the shoes. Thus, a topological sort of your morning routine must have socks appear first before shoes.

The edges in the DAG represent dependencies between the tasks. In this example above, that would mean that task A must be completed before tasks C and D, task B must be completed before tasks D and E, E before G, C and D before F, and finally F and G before H. A topological sort gives you an order in which you can do the tasks (it puts the tasks in a linear order). Informally, topological sort returns a sequence of the vertices in the graph that doesn’t violate the dependencies between any two vertices.

Discussion: Topological Sorts and DAG’s

Why can we only perform topological sorts on DAG’s? Think about the two properties of DAG’s and how that relates with our “to-do list” analogy. Discuss your thoughts with your partner.

The Topological Sort Algorithm

The algorithm for taking a graph and finding a topological sort uses an array named currentInDegree with one element per vertex. currentInDegree[v] is initialized with the in-degree of each vertex v.

The algorithm also uses a fringe. The fringe is initialized with all vertices whose in-degree is 0. When a vertex is popped off the fringe and added to a results list, the currentInDegree value of its neighbors are reduced by 1. Then the fringe is updated again with vertices whose in-degree is now 0.

Exercise: TopologicalIterator

Implement the TopologicalIterator class so that it successively returns vertices in topological order as described above. The TopologicalIterator class will resemble the DFSIterator class, except that it will use a currentInDegree array as described above, and instead of pushing unvisited vertices on the stack, it will push only vertices whose in-degree is 0. Try to walk through this algorithm, where you successively process vertices with in-degrees of 0, on our DAG example above.

If you’re having trouble passing the autograder tests for the topological traversals, think about the effect of duplicate values in the fringe on your iterator. Try constructing a complete graph, and testing your DFSIterator on that!

Conclusion

Deliverables

- Complete the following methods of the

Graphclass:addEdgeaddUndirectedEdgeisAdjacentneighborsinDegreepathExistspath

- Complete the implementations of the following nested iterator:

TopologicalIterator